What the blurb tells us:

Mr. Pooter is a man of modest ambition, content with his clerkly lot. So why is he always in trouble with disagreeable tradesmen, impudent young clerks and wayward friends? And what is he to do about his son Lupin’s distinctly unsuitable choice of bride? However hard he tries, life piles its little mishaps on his head – but he’s not about to give up.

The Diary of a Nobody is a sharp, hilarious satire of suburban values and remains as pertinent now as it was when it was first published more than a hundred years ago.

Life is what you make it

Mr. Charles Pooter leads the ordinary life of the lower middle class in late 19th century England. He is a devout husband, a humble employee, and a respected father and friend — at least he likes to think of himself this way. For some 15 months he keeps his diary, cherishing good experiences, pondering about the bad stuff, and in general wondering how and why the world changes and with it a lot of things he took for granted. It seems that every day living a respectable life gets a little more challenging.

May 9: The Blackfriars Bi-weekly News contains a long list of the guests at the Mansion House Ball. Disappointed to find our names omitted, though Farmerson’s is in plainly enough with M.L.L. after it, whatever that may mean. More than vexed, because we had ordered a dozen copies to send to our friends. Wrote to the Blackfriars Bi-weekly News, pointing out their omission.

May 12: Got a single copy of the Blackfriars Bi-weekly News. There was a short list of seceral names they had omitted; but the stupid people had mentioned our names as “Mr and Mrs C. Porter.” Most annoying! Wrote again and I took particular care to write our name in capital letters, POOTER, so that there should be no possible mistake this time.

May 16: Absolutely disgusted on opening the Blackfriars Bi-weekly News of today, to find the following paragraph: “We have received two letters from Mr and Mrs Charles Pewter, requesting us to announce the important fact that they were at the Mansion House Ball.”

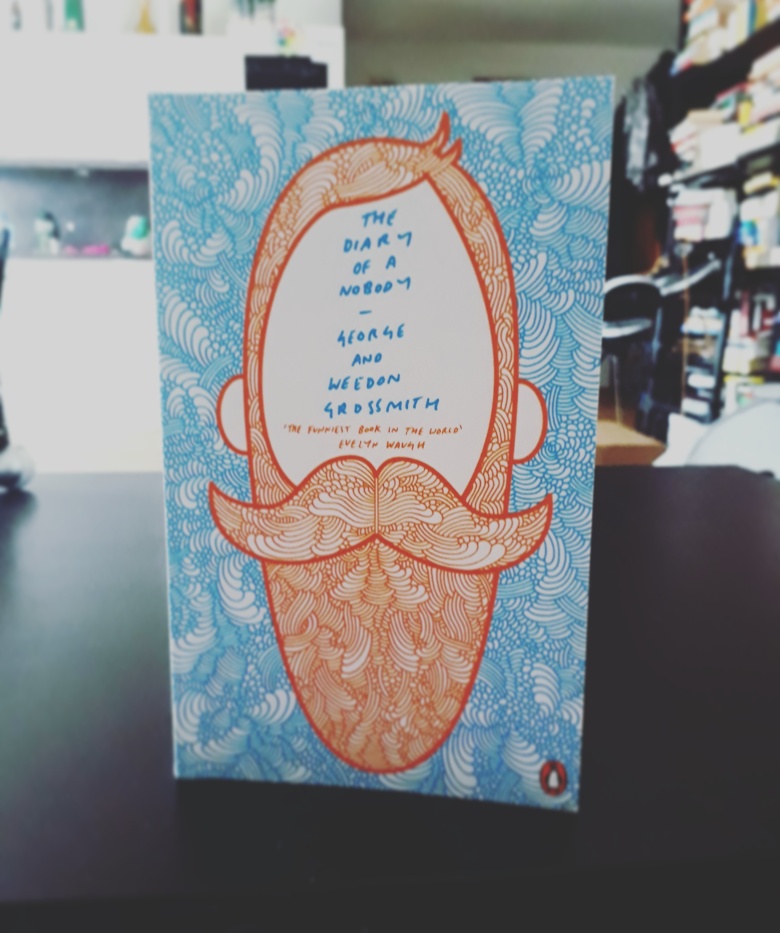

Written by George Grossmith and his younger brother Weedon — who also provided the illustration for the book — The Diary of a Nobody was first printed as a serial in Punch magazine in 1888-89 before being published as a novel in 1892. Its description of the everyday life of the lower middle class in England in the late 19th century allows us to witness trivial to comical dramas regarding a family and social life that is nothing less than comfortable. With our main character, Mr. Charles Pooter, constantly overestimating his own importance, he is prone to experience repeated disappointments when it becomes obvious — more to the reader than to himself — that the rest of the world does not share his hyperbolic self-image.

A cause for concern is the conduct of Pooter’s only son Lupin — actually called William, but opting to use his middle name Lupin —, who at 20 is still trying to find his place in this world. A sentiment that is quite common nowadays, for Charles Pooter in the 1880s it is a sign that his offspring fails to show the same steady dedication towards one career path as he does. Having worked for the same company for the last 20-something years, Mr. Pooter does his best to get Lupin back on track, even going so far as getting him a position in the same company he’s working for — which (surprise surprise) doesn’t end well. However, by the end of the book, we learn Lupin follows his own path, skillfully avoiding the average and humdrum life his parents are leading.

Sort of literary time travel

I love literature from the late 19th and early 20th century Britain, when every oh so simple novel can also be seen as a testimony to British imperialism in full bloom. It’s like a history lesson in literary form. However, in this novel, the focus is on the importance of class and social standing, with the world outside of Britain being less of a topic. Reading it, I had to pause several times to ‘improve’ my language skills and historical knowledge — researching dress codes, vehicles, professions, and vernacular that are hard to grasp nowadays, especially for non-native speakers. Anyway, having read works by writers like the Bronte sisters, Jane Austen, and Arthur Conan Doyle, I found my way around the lesser known expressions and enjoyed the comical misadventures of Mr. Pooter and his family.

Even though pretending that he does not think himself to be of any importance, when musing about how his diary might be published after his death, it becomes evident that the opposite is true. Deeming his writings important enough to publish them posthumously shows his high level of self-importance. Only reality and the mishaps that come with having family, friends, and a life in general keep him from actually living up to what he deems is rightfully his position in society. Everyone has his/her place, one has to follow rules and social order. That not even his son follows these restrictions Pooter himself observes so critically is reason enough to deem the boy inadequate. It also shows the obviously age-old disparity between young and old, parents and offspring. Be it 1889, 1982, or 2012 — kids seem to keep their parents constantly worried no matter which century.

Referencing people and events of their time, the authors challenge their modern readers who are less familiar with life in Victorian England. Regardless, the humor and insights this book shares by far outweighs the occasional hurdle of lacking specific historical knowledge. If you ever wanted to read a diary that is neither puberty-cliche-ridden, dramatic, and/or your own, then this is an excellent choice to start. Hope you enjoy it!