I haven’t the courage, or perhaps the hardness, to withstand the tremendous pathos of this life. I love life’s casual beauty — fear its awful strength.

— Jack Kerouac The Sea is my Brother

What the blurb tells us:

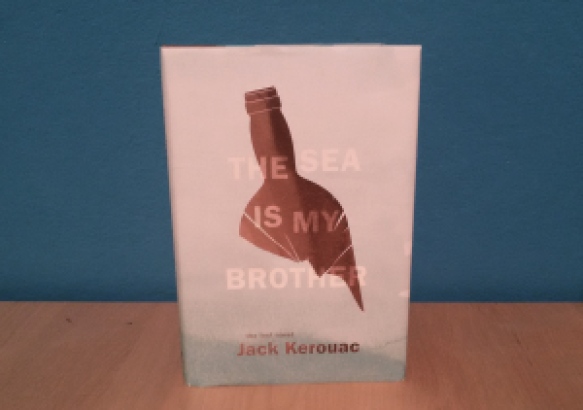

In the spring of 1943, not long after his first tour as a Merchant Marine, twenty-one-year-old Jack Kerouac set out to write his first novel. Working diligently day and night to complete it by hand, he titled it The Sea is my Brother, and described it as a novel about “man’s simple revolt from society as it is, with the inequalities, frustration, and self-inflicted agonies.”

[…] it is an important formative novelthat bears all the hallmarks of classic Kerouac: the search for spiritual meaning in a materialistic world, spontaneous travel as the true road to freedom, late nights in bars and apartments engaged in intense conversation, the desperate urge to escape from society, and the strange, terrible beauty of loneliness.

Now let’s move on to see what I make of this… 🙂

Not a believer

As working on my talk (yes, still working on it…) and some other serious stuff kept me from writing earlier, I will post this as a sort of follow-up post to my previous thoughts on Jack Kerouac and his writing that I read and enjoyed it throughout the years.

The last time I read Jack’s work was years ago, one of his more spiritual (or rather, religious) writings, Wake-Up, A Life of the Buddha. Since I’ve never been much of a religious person, I did not finish this book. I know some argue that Buddhism and the legend of Buddha do not resemble the traditional understanding of religion. However, I have a hard time believing in any sort of spiritual entity (or entities, to stay open-minded) ‘magically’ influencing my life in any way. To be more precise and honest, I’ve always had my problems with the concept of ‘belief’ and ‘believing’, no matter if religious, spiritual, or general. I did not ‘manifest’ Brexit nor do I ‘believe’ in the second (or third, or fourth,…) coming. So the fact that I never finished Jack’s spiritual musings is not surprising.

Still a reader

When I started reading Kerouac once more – again a “long-lost” novel by this icon of the Beat literature – I wanted to get some information about The Sea is my Brother as well as The Haunted Life. After all, Jack seems to be part of the Tupac Shakur/Kurt Cobain-phenomenon, which proves that no matter when and how you died, you are never too dead to release new music or publish a new book. Always love the cash cow.

Researching the origins of the ‘rediscovered’ books, I found a review of The Sea is my Brother in the Los Angeles Review of Books which was very informative and entertaining. It also reinforced my first impression of the book — as the reviewer stated, Kerouac never wanted this book to be published, and I definitely understand why. It is not that The Sea is my Brother is bad — it is not. Rather, it’s a bit crude, to put it bluntly.

Kerouac has always been known as a highly autobiographical writer; all the beats are as much storytellers as they are chroniclers in their various ways. Following this pattern, he liked to play with his real-life influences by connecting characters and events in different ways. This may lead his audience to perceive a sort of recycling that can be irritating and funny at the same time. For example, those who read The Town and the City will rediscover not only familiar names but also characters in The Haunted Life and The Sea is my Brother.

Deja vu, anyone?

In The Sea is my Brother, Wesley Martin, the oldest of the Martin family that we encounter in The Town and the City, works as a sailor without much ties to family and friends apart from fellow seamen. He is portrayed as an easygoing, lighthearted guy, preferring emotional detachment regarding his relationships with women, while forming strong bonds with male companions, especially fellow seamen. He is, of course, just one of many protagonists that are alter egos of Jack himself.

The strong emphasis on male bonding is very dominant in this novel (or rather, fragmentary novel?), as it is in most of Kerouac’s writing, though not always as blatant. Apart from foreshadowing Kerouac’s main literary tropes, Wesley also seems to have a talent for running into highly intelligent, politically committed, academic babblers, in this case, Bill Everhart, who later joins him on a vessel. Though there are various character keys for Kerouac’s novels online I could not find a definitive reference regarding Everhart’s real-life model, though I suspect it could be William S. Burroughs (please feel free to correct me if you have better ideas!).

Aside from Bill babbling a lot and Wesley constantly being on the run from himself (therefore seeming to be detached from everyone in the story apart from the sea) the recurring incoherencies in the writing itself result in a novel that is at times hard to read. Having finished it just now, I indeed understand Jack’s wish to not have this novel published. As he was very meticulous about his writing, his characters, and his storytelling throughout his life, this novel does not live up to everyone’s expectations.

But, as Merve Emre in her aforementioned LARB review so poignantly states, Jack Kerouac is a brand, a household name, which promises high profits, no matter how low the actual effort is. She is, of course, right. After all, I too bought the book (and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only ‘Beat literature enthusiast’ out there…).

Let’s stick to Jack’s earlier writing instead, or at least the books he wanted us to read. Might be more fun…