What the blurb tells us:

When Chris Kraus, an unsuccessful artist pushing forty, spends an evening with a rogue academic named Dick, she falls madly and inexplicably in love, enlisting her husband in her haunted pursuit. Dick proposes a kind of game between them, but when he fails to answer their letters Chris continues alone, transforming an adolescent infatuation into a new form of philosophy. Blurring the lines of fiction, essay and memoir, I Love Dick is widely considered to be the most important feminist novel of the past two decades.

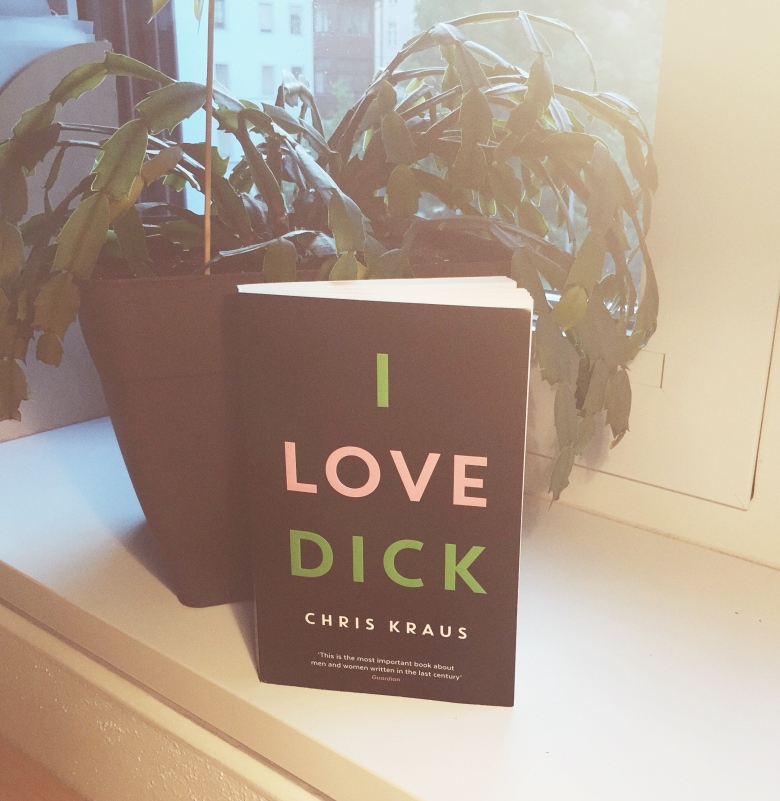

I didn’t know anything about this book apart from seeing it on bookstagram a lot, so when I read the Guardian‘s remark on the cover about this being “the most important book about men and women written in the last century,” I had quite some expectations. Alas, dear Guardian, I have to politely disagree. Though I haven’t read that many books about men and women “in the last century”, I still believe there’s more out there, somewhere, probably less hyped and prominent yet infinitely more interesting. Besides, this was probably too much of a praise for one author and her book to live up to.

Don’t be a…Dick?

The point of departure for this literary tour de force is an evening Chris Kraus — a 39-year-old, failed artist who is successful as being a savvy and (self-)educated wife of an French academic and intellectual — and Sylvère Lotringer — said French intellectual and academic, her husband — spend with an acquaintance of Sylvère, Dick (who was later identified as the cultural critic Dick Hebdige). Dick seems to be flirting with Chris throughout the evening, and after initially being irritated, she feels excited and empowered, enough so to eventually fall in love with him — or is it love? Desire? Obsession? Whatever it is, it serves as a reason for the author to examine her own past as well as the his(her)story of male and female artists, thinkers, authors, and philosophers in regard to modern feminism and the (art) world.

To see yourself as who you were ten years ago can be very strange indeed.

The people mentioned here – Chris, Sylvère, and Dick – are all real, they exist in our world and are not mere characters in a novel. In what sense these ‘real’ people correlate with the characters in this book is unclear and — to me at least — irrelevant. Chris Kraus’ I love Dick is neither a conventional novel, as you may have guessed by now, nor a memoir, but rather something Joan Hawkins in the afterword of the 2016 edition calls ‘theoretical fiction’, which sums it up pretty nicely.

Chris jumps from the early 80s to the mid-90s to 1992 to 1995 and back; she leaves her husband, only to be with him again in the next passage and then she is with someone else. She regularly connects theoretical, philosophical, historical, and gender perspectives with her own story, the people she knew, read, watched, or heard of. While this regularly interrupts the storyline, it was also the thing I liked most about the book. It is full of information about artists, thinkers, philosophers, and authors, male and female, their lives, works, and passions. However, this constant switching between a sort of actual narration and her theoretical explanations regarding certain topics, often with a feminist background, also got quite confusing and overwhelming sometimes. Now and then it just took me some time to actually recognize another shift of focus and I felt lost for the moment; that’s not necessarily bad but it CAN be unnerving…

Alas, another ‘difficult woman’ to learn from

Most of all, I enjoyed Kraus’ discussion of feminist issues. Doing so, she keeps it open-minded and down-to-earth, elaborating on various problems a lot of female artists and thinkers faced and still face (even today). Quoting the American poet Alice Notley she declares:

Because we rejected a certain kind of critical language, people just assumed that we were dumb.

And even in 2018, I can still relate to this quote in an academic and a professional context. Exploring how being a woman and deciding to live independently — be it in a professional, personal, or artistic understanding — can influence our whole existence in all its various facets was interesting and by far the best about this book, at least for me.

But there were also times I simply didn’t ‘get’ her (this was actually quite often…). I’m rather the down-to-earth and practical kind of person, so some of her forays into the world of art and theory were simply too abstract for me. Additionally, since this is a sort of theoretical fiction with a lot of essayistic sections, there is actually the possibility to disagree with the author — see here for yourself (and disagree with me, for that matter):

The philosopher Luce Irigaray thinks there is no female “I” in existing (patriarchal) language. She proved it once by bursting into tears while lecturing in a conference on Saussure at Columbia University.

Let me tell you: I too was close to tears last December when I gave a lecture at Columbia University, though not because my female “I” felt misunderstood and lonely within this system of patriarchal language but rather because of stress, anxiety, and being close to a panic attack. Still, I can understand that one cries while giving a lecture about Saussure (who is very interesting, but also very male, especially in regard to Luce Irigaray’s line of thought) at Columbia; but this “proves” nothing, especially not something the philosopher is/was “thinking.” “Proved” doesn’t work for me in this context and I would love to know more about what had exactly happened to as to understand better why Irigaray was in need to “prove” anything.

I’ve read Irigaray, and she’s much too theoretical and high-strung for me (I’m not a linguist); as long as women still face male (and societal) aggression in a lot of ways every day and everywhere as well as a huge gender pay gap, I don’t care all that much about the female “I” in our patriarchal language (though of course I know that this is an important issue — it’s just a question of priorities, and mine differ from those of Irigaray and like-minded feminists). Though this is just a small paragraph at the end of the book, I found it highly irritating, probably because it is a very narrow-minded conclusion for someone as open as Kraus seems to be throughout the rest of her book.

Interesting, overwhelming, educational

I love Dick was interesting, confusing, multilayered and at times fascinating. The ‘love story’ of Chris and Dick opens up the discussion of much more important things, especially regarding Chris’ self-discovery and her relationship to the world around her. There’s hardly any interaction between the Chris and Dick, the main male voice we hear is Sylvére’s.

Because of the different styles of narration — third person narration, first person narration, emails, letters, diary entries — I had my difficulties getting ‘into’ the story. I read three pages, then I suddenly remembered I had to water the plants, look after the cat, clean some dishes, read/write an email, shave my legs, eat something, drink something, use the bathroom, check on the cat again…you get the picture. I love Dick wasn’t much of a captivating reading experience BUT it was still interesting. I learned a lot, and as we all know, I love learning. Yet, I do think there are more important books “about men and women written in the last century” out there…