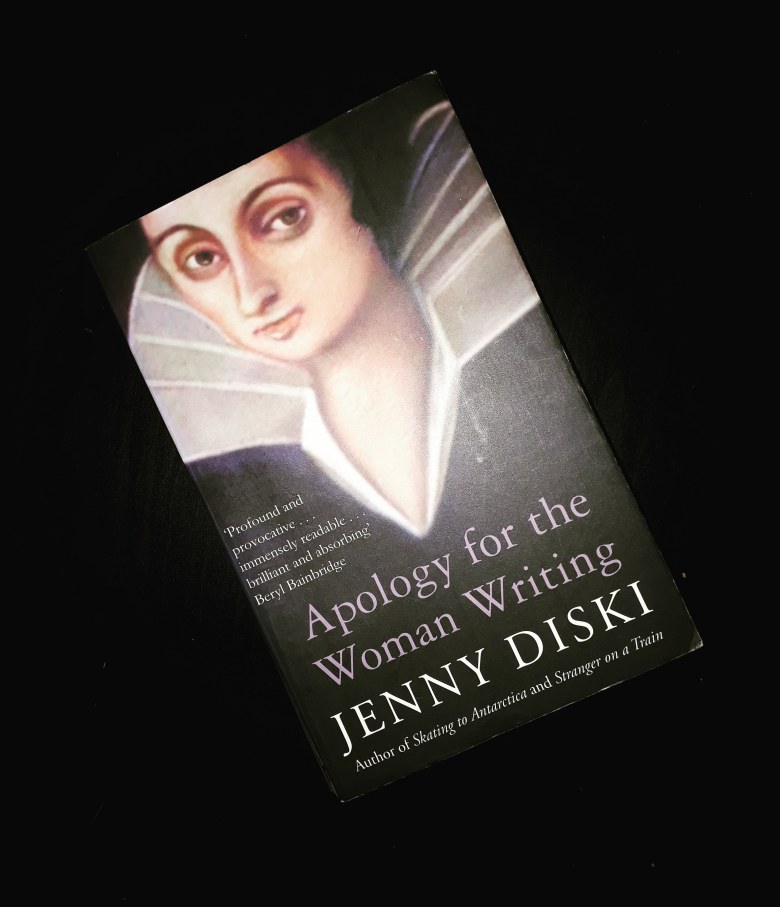

What the blurb says:

So overwhelmed was Marie de Gournay by the work of French essayist and philosopher Michel de Montaigne that when she finally met him, she stabbed herself with a hairpin until the blood ran in order to show her devotion. An awkward, obsessive character, she set herself against the world in her determination to achieve her ambitious dreams. Only her servant, Jamyn, really knew her.

— Jenny Diski Apology for the Woman Writing

Rewriting the life story of France’s very first feminist (probably), Marie de Gournay, Jenny Diski illustrates the struggles of early feminism and the first pursuits of women to live and exist as a person of their own, not just a daughter, a wife, or a mother. Not writing a biography but a novel based on real-life characters, Diski’s Montaigne seems larger than life only to be nothing more than just another “man like any other,” however much Marie idolizes him into a greatness no one could live up to, least of all Montaigne himself.

A woman reading

Diski’s Marie is a stubborn, passionate, and sometimes aloof woman, who is in no way interested in following the well-worn paths of her mother and the women of her times. Marie wants more for herself. She sees no reason to follow her mother’s wishes or obey society’s idea of what a good woman of her time should be.

Her father’s library in Gournay was the place of escape from her present and from her preordained future. She slipped through the dark panelled door at every possible moment of the day and night, whenever she could avoid being tutored on how to be someone’s wife, some house’s keeper, some child’s mother.

Being an avid reader and aspiring philosopher, it comes as no surprise that Marie finds her calling in the world of books, libraries, and thoughts when being gifted a copy of Michel de Montaigne’s Essays by her uncle Louis.

‘I’m not ill, Maman,’ she whispered, still breathing fast, her face changed from dead white and vivd pink to the yellowish pale of parchment. ‘It’s Monsieur de Montaigne. He has ravished me.’ There was a gasp from the three other women, each of whom instantly reassessed their usual picture of Marie in the library. ‘His books … the ones Uncle Louis gave me … they are … extraordinary … I’ve never imagined … they are … remarkable. No, remarkable is too small a word. Nothing, nothing, in all my life I’ve read nothing like these essays.’

The Master and Marie

Diski’s Marie devotes her life and existence to the work and (later) legacy of Michel de Montaigne and his Essays. Setting out to become a writer and philosopher herself — something unthinkable for a woman in the French upper-class of those days — she eventually moves to Paris (first with her family, years later on her own) to try her luck. Diski portrays Marie as an ambitious scholar, an autodidact who challenges her intellect with the works she finds in her late father’s library and the books her uncle shares with her, but also as a woman with a lack of female looks and features. In this instance, Marie can seem like a caricature, though later in the book it becomes clear that she is indeed savvy enough to organize her house on a tight budget, so she is at least a bit practical, albeit not in the traditional female way of those days.

Reading Montaigne’s Essays, Marie seems to have found her true calling, becoming one of history’s first ‘groupie’ and existing solely to promote and support Montaigne’s genius, even though in the beginning he doesn’t even know her. After falsely believing that he is already dead, she writes him a passionate letter when finding out he is still alive and well and in Paris, where she is as well. Montaigne, after reading her ardent words, imagines a beautiful and devoted young woman and decides that he wants to meet her. So during her first stay in Paris, Michel de Montaigne pays Marie a courtesy visit. This unsettles her deeply, furthering her devotion to the great master. He, too, is quite shaken by this meeting, realizing that this young woman is not what he imagined and wished for, especially concerning her looks. Not noticing the irritation caused by her person and demonstration of admiration — she pinches herself with a hair pin until he bleeds to show her ‘love’ for him — Marie invites Montaigne to stay at her family’s home, the Chateau de Gournay, whenever he feels like it.

After accepting her as his “fille d’alliance”, a “daughter of his intellect” — a compromise after she wanted him to adopt her and he thought briefly of ignoring her lack of good looks for some youthful moments of lust — he didn’t want to meet her again. Yet he is forced to accept her invitation to Chateau de Gournay when suffering from a heavy bout of gout on his way home from Paris. Staying for several weeks, Marie and Montaigne revise his Essays and it is then that she experiences her biggest triumph, seeing how he includes a paragraph of appreciation for her and her writing in his work. This paragraph, this moment of recognition from her mentor, will keep her going to the end of her days. This is what will make her vulnerable and, occasionally, the subject of ridicule in Paris society, even though she does not see it.

Already she was using his name to boost her own work. A devotion to Montaigne’s work would replace the husband she would never have, the quality work she would never produce, and the restricted life she must inevitably lead. So there was something in it for her, as well as for him and his memory. He decided to speak to Francoise about it, and ask her to send a farewell letter to La Demoiselle as if dictated by him. And yes, he knew how close this thought was to a crime against her. A further crime. He would have liked to think that he was not a dishonest man. But he was, after all, a man like any other.

A woman writing

Reading Diski’s retelling of Marie’s life, one would think this woman hardly wrote anything original apart from commentary on Montaigne’s work. Nevertheless, she still also worked on her own books and essays as well, even though Diski does not focus on this part of Marie’s life and work as much as her fangirling concerning Montaigne. This underlines the affiliation a woman needs to have in order to succeed, the direct connection to a man, not any man but an established person of public interest, a name that gains her entry into literary circles and interest from those who will eventually sustain her own work. Because as a woman of the late Renaissance era, Maria accomplished quite a lot: writing for nobility, receiving an allowance by Queen Margo, recognition from an important thinker and writer, publishing her own writing. Everything that is remarkable about Marie as a person — her stubbornness, her dedication to learning and constantly working on her skills — makes her work average and uninspired in the eyes of Montaigne and the voice of Diski.

After Montaigne’s death, Marie’s misguided self-assessment climaxes when she revises the final edition of his Essays, acting contrary to the request of Montaigne’s widow who, in accordance to his will, simply asks her to find a printer in Paris to publish further editions of his work in his honor. Acting on her grievance, Montaigne’s widow opposes Marie’s additions and revisions and wants nothing more to do with her. Realizing that she may have overestimated her position in Montaigne’s life and work, she finally comes to terms with creating a life and writing of her own — which is when Diski introduces us to a woman who is coming to terms with working on her own terms with her own ideas and thoughts. This is Marie without Montaigne, Marie on her own, Marie with Jamyn, her maid, another woman who is capable of so much more than she truly shows. Also, Diski adds an interesting twist to the relationship of the two women, which could be seen as a lazy cliche, but also adds an important and interesting layer to Marie’s character.

In the “Author’s note” Jenny Diski calls her work a ‘historical novel’ and discusses her sources — mainly Marjorie Henry Ilsley’s Daughter of the Renaissance — and inspirations for her fictional Marie. Since the letters between Montaigne and Marie — if they ever existed — have not survived, Diski focuses on biographical dates and the little information there is, filling the huge gaps with her version of Marie’s life. And what a life this is. Marie can be annoying at times, her fangirling and the way she never sees how her beloved philosopher often uses her can be exhausting. But I don’t have to love the main character to appreciate and like a book. Often, the characters that challenge us are the ones that stay with us for quite some time.